Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in cats is progressive and not curable but there are strategies we can undertake to improve the quality of life of our “kidney” cats and possibly give them some more time with us. Here is a checklist for managing the cat with chronic kidney disease:

- Keep Kitty hydrated

- Feed a diet that will lessen the stress on the kidneys

- Maintain appetite

- Manage high blood pressure

- Treat anemia if necessary

- Treat urinary tract infections

Managing the cat with chronic kidney disease

hydration

Kidney failure is tied to the “death” of nephrons that filter the blood. The remaining nephrons compensate by increasing filtration. Dehydration decreases renal blood flow putting more stress on the remaining nephrons. Keeping the “kidney” cat hydrated helps maintain electrolyte concentrations and dilute the waste products the kidneys are struggling to filter out.

Increasing Voluntary Water Intake

- Have a variety of water sources and fountains in the home to encourage water intake.

- Consider feeding a wet diet – many canned foods contain about 80% water.

- Try water from tuna, water used to poach chicken or fish (offer alone, add to the water bowl, or try frozen in an ice cube tray and added to the water bowl).

Hydration supplements like Purina’s Hydra Care are designed to maximize the amount of water cats take in while drinking. Nutrient enriched water is more viscous, clings to the cat’s barbed tongue, and increases the water consumed with each lap of the tongue.

Subcutaneous Fluids

This refers to giving fluids under the skin, not in a vein. It is done using a bag of sterile fluids, an IV line and a needle. This is a strategy often employed in IRIS stages 3 and 4 of kidney disease. This can be done in the veterinary clinic or at home, once you and your cat are comfortable with the process.

Kidney-friendly diets

As the kidneys fail, they are no longer as efficient at filtering the waste products of protein metabolism. Phosphorus in the form of phosphates tends to build up in the body while potassium levels may drop.

Commercial renal diets for kidney cats feature reduced phosphorus and restricted amounts of high-quality protein, an increased calorie density, sodium restriction, potassium supplementation, supplementation with B vitamins, anti oxidants and omega-3 fatty acids (Reference 1). There have been a number of studies done addressing the effectiveness of these diets – the results show that cats suffering from CKD lived longer when fed a renal diet (Reference 2).

Phosphorus Binders

For some cats in advanced stages of CKD, a renal diet may not reduce phosphorus enough; other cats simply refuse to consume a renal diet. For these cats, adding a “binding agent” to the food can help reduce the amount of phosphorus that is available for the cat to metabolize. Supplements that “bind” with the phosphates in the food form a nonabsorbable compound eliminated in the stool. “Phosphorus binders” include (Reference 1):

- Aluminum hydroxide

- Calcium carbonate

- Calcium acetate

- Sevalamer (a hydrogel of poly-allylamine, free of aluminum and calcium)

appetite and nausea

A “kidney” cat can suffer from nausea and vomiting due to the buildup of uremic toxins in the bloodstream. The cat consequently doesn’t eat well resulting in dehydration and weight loss. Reduced potassium levels and anemia due to CKD also contribute to a reduced appetite (Reference 1).

Medical Management

Managing the cat with chronic kidney disease also includes managing nausea and vomiting. Drugs that target nausea and vomiting include maropitant (Cerenia) and ondansetron. These are typically available in oral tablets.

There is another drug that is often the first choice of many practitioners. Mirtazapine is an antidepressant drug that not only controls nausea and vomiting, it also stimulates appetite.

- available in a transdermal gel (Mirataz) as well as tablets

- the transdermal form is FDA approved for use in cats

- the transdermal gel is applied once daily and the dose is easily adjusted

- side effects are vocalizing and increased activity.

If a cat is too nauseous or unwell to maintain food intake, a feeding tube should be considered.

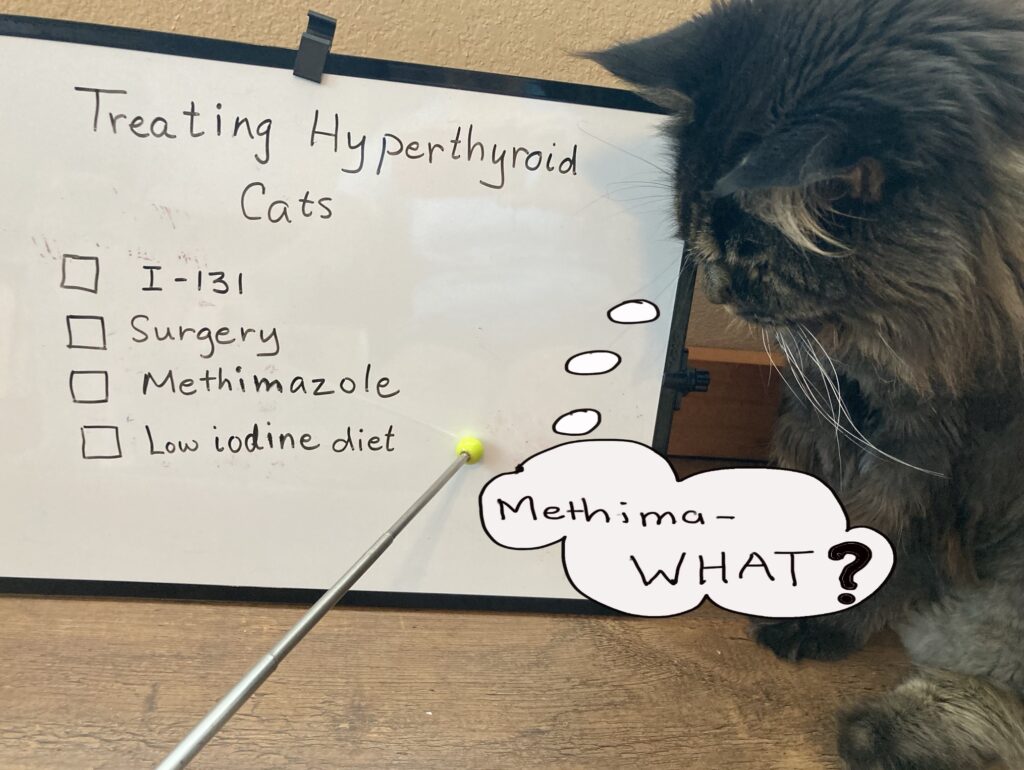

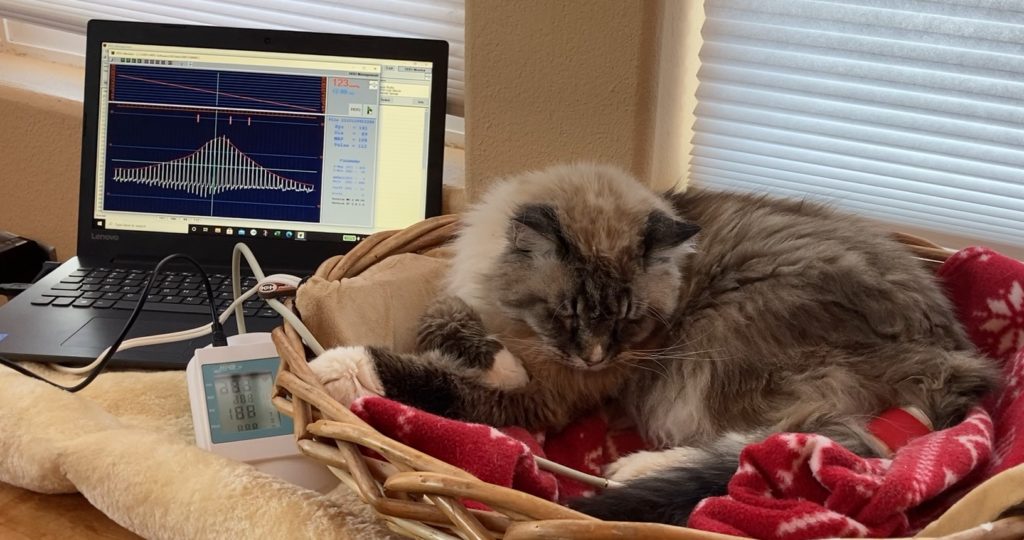

high blood pressure

Increased filtration rate in the remaining nephrons and activation of the renin-angiotensin system can lead to high blood pressure in cats with CKD. Systolic blood pressures over 160 mm Hg require treatment to prevent damage to the cat’s eyes, heart and kidneys. In particular, the leakage of proteins into the urine (proteinuria) can be reduced once high blood pressure is managed (Reference 1).

Amlodipine is the most commonly used drug to reduce cats’ blood pressure. It is a calcium channel blocker that is available in tablets that can be taken once or twice daily. Amlodipine typically reaches therapeutic levels in 7-10 days. Managing the cat with chronic kidney disease should include a blood pressure check every 3-6 months.

anemia

One of the kidney’s functions is to produce the hormone erythropoietin. Erythropoietin triggers cells in the bone marrow to make more red blood cells. Failing kidneys may not generate enough erythropoietin and anemia (low levels of red blood cells) can result.

Fewer red blood cells means less hemoglobin. Less hemoglobin means less oxygen is getting moved around the body. Anemia can result in weakness and tiredness.

If the fraction of red blood cells in the blood drops below 20%, many practitioners will supplement the cat with a man-made analog of erythropoietin. The most commonly used drug is darbepoetin; it is given as an injection under the skin. Injections of iron supplements often accompany the darbepoetin injections in the initial stages of therapy (Reference 1).

A new treatment (2023) is available for anemia in cats with CKD. Varenzin -CA1 is a once daily oral liquid medication made specifically for cats. Varenzin-CA1 is designed to stimulate the cat’s body to make its own erythropoetin.

Urinary tract infections (UTI)

With increasingly dilute urine seen in cats with CKD, UTI’s are more common. Most of these UTI’s do not have clinical signs such as frequent urination or blood in the urine. Urinalysis should be part of the CKD cat’s checkup. White blood cells found in a centrifuged urine sample are indications for a bacterial culture and treatment. Treatment can be based on sensitivity testing and a kidney friendly antibiotic chosen.

Managing the cat with chronic kidney disease requires attention to multiple factors. Treating dehydration, nausea, high blood pressure and anemia can keep the “kidney” cat comfortable and slow the progression of the disease. A critical part of managing the cat with chronic kidney disease is feeding an appropriate diet. The next post will look at the science behind the commercial renal diets and alternatives to them.

references

- Sparkes, A. (panel chair), ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Feline Chronic Kidney Disease, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2016) 18, 219–239.

- Quimby, J. and Ross, S., Diets for Cats with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) [updated 2022]. http://www.iris-kidney.com/education/protein_restriction_feline_ckd.html [viewed 9/2023]