You are juggling your keys and a few bags of groceries as you approach your front door. You turn the key in the lock and open the door. In that instant, your cat slips out and melts into the darkness. Several scenarios run through your mind, each worse than the one before: she’ll get lost, hit by car or eaten by a coyote. How do you keep your cat from running outside?

You are juggling your keys and a few bags of groceries as you approach your front door. You turn the key in the lock and open the door. In that instant, your cat slips out and melts into the darkness. Several scenarios run through your mind, each worse than the one before: she’ll get lost, hit by car or eaten by a coyote. How do you keep your cat from running outside?

KEEP YOUR CAT FROM RUNNING OUTSIDE

The outdoors holds many attractions for a cat: butterflies to chase, grass to munch on, and sights and sounds that call to a cat’s “inner hunter”. How do you keep your cat from running outside?

physical barriers

- There are extra tall cat gates to block doorways that lead to that appealing front door. But these only work if humans keep them closed.

- PetSafe markets an electronic barrier that beeps then gives a low static “correction” (shock) to contain both cats and dogs in certain areas of the home.

- Although there have been several studies concluding that electronic fences do not reduce a cat’s quality of life, cats have been known to run through a barrier while chasing prey, then be reluctant to return through the electric field. Also, electronic fences won’t work if the power is out (References 1, 2).

teaching substitute behaviors

Teaching your cat to do something else when the door opens can help keep your cat from running outside.

- Place a high cat tree near the doorway and train your cat to go to the cat tree when she hears the jingle of keys in the hallway. She can await your return and a reward! (see “Desensitizing Your Cat to the Sound of the Doorbell”)

- A remote treat dispenser such as a PetCube can also help – when you are close to the door, you can cue your cat to go get a treat in a place away from the door.

TEACHING YOUR CAT TO MANAGE HIMSELF OUTSIDE THE HOME

We fear for our cats’ safety when they dash out the door. In rural and urban areas, predators such as coyotes abound. Busy roads can spell death to an unlucky cat. Spilled antifreeze is very toxic to cats resulting in kidney damage even if they are treated promptly. The shorter the time the loose cat spends on the run, the better.

Outdoor cats create a scent and auditory map of their home territory so that they can return to that place where it is safe to eat, eliminate and rest. There is some evidence that cats may be able to use the earth’s magnetic field to locate their home (Reference 3).

So, if possible, supervised walks near your home (or even in your apartment hallway if it is permitted) can help your cat form this mental map. The walks can also satisfy your cat’s curiosity about what’s on the other side of the door. The harness and leash are a cue that she is going out and can help keep your cat from running outside.

An essential skill for any cat is recall – train your cat to come when called. This can be invaluable if the worst happens and he somehow gets away. He most likely will hide and not respond at first – give him some time to calm down and let his training kick in. Keep calling him or giving him his recall cue.

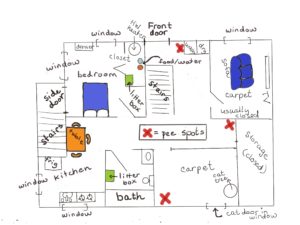

tux, an escape artist

One of the clinic cats at the vet clinic where I work is fond of the outdoors. After a few forays outside with one of our assistants, Tux saw that the front door opened frequently and that there was often enough time for him to slip through as a client struggled though the door with a cat carrier. This began to happen more frequently resulting in someone stopping by to tell the receptionists that there was a black and white cat sitting on the grass outside the clinic door!

A Plan for Tux

- Restrict Tux from the lobby (and the front door) (physical barrier).

- Allow Tux supervised walks on a leash and harness (train a substitute behavior).

- Build an association with the harness and leash and the outdoors – the harness would be the cue to let Tux know it is walk time (No harness – no outdoors).

- Use the side door to go on supervised walks on a harness and leash (reduce the association with the front door and the outside).

As the weeks have passed, Tux has begun to take charge. He comes willingly to be harnessed and aims for the side door. He enjoys the fresh air and grass. A few Temptations help guide him along. With regular walks, he is not monitoring the front door as much – if the interior doors to the lobby are open, he does not always make a beeline for them.

Physical barriers can help keep your cat safe. Electronic “fences” are available to contain your cat but are a bit controversial. These barriers are not foolproof – they depend on keeping the gate shut or the power being on. Giving your cat the experience of what is outside the front door can help satisfy her curiosity and help keep your cat from running outside. If your cat does slip by, she is familiar with the territory and should be able to make her way back.

references

- Kasbaoui N, Cooper J, Mills DS, Burman O. Effects of Long-Term Exposure to an Electronic Containment System on the Behaviour and Welfare of Domestic Cats. PLoS One. 2016 Sep 7;11(9):e0162073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162073. PMID: 27602572; PMCID: PMC5014424.

- Santos de Asis, L and Mills, D. Introducing a Controlled Outdoor Environment Impacts Positively in Cat Welfare and Owner Concerns: The Use of a New Feline Welfare Assessment Tool. Front. Vet. Sci., 10 January 2021. Sec. Animal Behavior and Welfare Volume 7 – 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.599284

- Mitchell, Sandra C., Can Cats Find Their Way Home? petMD updated August 18, 2022, petMD. https://www.petmd.com/cat/care/can-cats-find-their-way-home, viewed 7/2024

Want to keep up with the world of cats? Subscribe to The Feline Purrspective!

Touch is important for many species. It is often part of a social interaction, cementing bonds between the members of a group. Primates (chimps, baboons,…) groom each other; dogs groom each other, birds preen each other as part of courtship or bonding. Domestic cats also groom and rub against each other in greeting.

Touch is important for many species. It is often part of a social interaction, cementing bonds between the members of a group. Primates (chimps, baboons,…) groom each other; dogs groom each other, birds preen each other as part of courtship or bonding. Domestic cats also groom and rub against each other in greeting.

Whether you are relocating or just visiting extended family, flying with your cat requires planning and preparation.

Whether you are relocating or just visiting extended family, flying with your cat requires planning and preparation.

Sometimes, fear and anxiety can make it difficult for a cat to cope with her daily life. Perhaps there has been a change in the environment – a new cat or dog comes to live in the home or a new born baby comes home one day.

Sometimes, fear and anxiety can make it difficult for a cat to cope with her daily life. Perhaps there has been a change in the environment – a new cat or dog comes to live in the home or a new born baby comes home one day.

The Feline Grimace Scale (FGS) provides cat owners with a way of assessing acute pain. The FGS focuses on 5 features of the cat’s face: position of the ears, shape of the eyes, shape of the muzzle, attitude of the whiskers, and position of the head. The user assigns each feature a score of 0 (no pain), 1 (moderate pain), or 2 (obvious pain) for a maximum of 10 points. A score of 4 indicates that the cat is painful. To use the FGS, see

The Feline Grimace Scale (FGS) provides cat owners with a way of assessing acute pain. The FGS focuses on 5 features of the cat’s face: position of the ears, shape of the eyes, shape of the muzzle, attitude of the whiskers, and position of the head. The user assigns each feature a score of 0 (no pain), 1 (moderate pain), or 2 (obvious pain) for a maximum of 10 points. A score of 4 indicates that the cat is painful. To use the FGS, see