Over 10% of cats over 8 years old will be diagnosed with hyperthyroidism in their lives. Although evidence points to thyroid disrupting chemicals in the cats’ food and environment, we don’t really know why these cats will become hyperthyroid. Prompt diagnosis and treatment will help these cats live long and healthy lives.

Diagnosing and Treating Hyperthyroidism in Cats

Diagnosing

Clinical signs of hyperthyroidism include increased appetite and weight loss. These signs progress slowly and it may be months to years before the cat owner realizes that something is wrong.

Cats are considered seniors at the age of seven. Regular lab work is recommended for senior cats and most senior feline blood panels include a thyroid hormone (T4) measurement. Persistently elevated T4 concentrations coupled with one or more of the classic clinical signs (below) at the same time often confirms the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism. (Reference 1)

- weight loss

- increased thirst and urination

- increased vocalization

- hyperactivity

- rapid pulse and breathing

- vomiting, diarrhea

- unkempt hair coat

This list of clinical signs is also shared with other feline diseases, such as diabetes, kidney disease, and GI disorders. These diseases can lower the T4 measurement, so that it is in the reference range, making diagnosis of hyperthyroidism challenging.

a challenging diagnosis

Cats that may have kidney disease as well as hyperthyroidism are particularly challenging to diagnose. Thyroid hormone increases the blood flow through the kidneys, often lowering kidney values to within the reference ranges. At the same time, kidney disease impairs the binding of T4 to proteins, reducing the T4 concentration. One disease masks the other and vice versa (Reference 2).

Cats with borderline T4 values and those suspected of having another chronic disease will need additional testing before a definitive diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is made. The veterinarian may request a more sensitive test called a “free T4 by equilibrium dialysis” in addition to remeasuring total T4. “Free T4” measures a form of T4 that is not bound to proteins in the blood. (Reference 3)

Routine thyroid monitoring in humans and dogs measures levels of TSH or thyroid stimulating hormone. Unfortunately, levels of TSH in hyperthyroid cats are often too low to be detected using canine tests. Zomedica has recently developed a feline TSH assay capable of measuring the low levels of TSH in cats which may aid in diagnosing feline hyperthyroidism. (Reference 3)

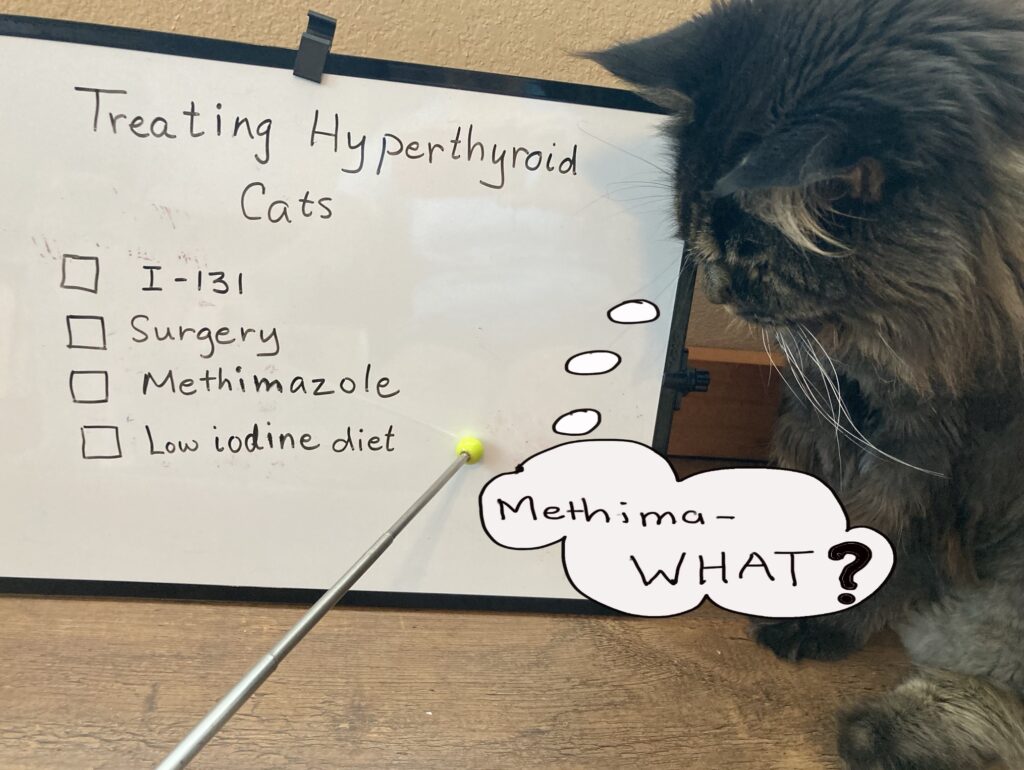

treating hyperthyroidism in cats

At the present time, there are 4 treatments available to cats with hyperthyroidism (Reference 1).

- radioactive iodine (I-131)

- medical management with a drug called methimazole

- surgical removal of abnormal thyroid tissue

- dietary therapy using iodine-restricted food

1. Radioactive Iodine (I-131)

Treating hyperthyroidism in cats with radiation must be done at a licensed facility. An injection of radioactive iodine is given under the skin, like a vaccine. The cat stays at the facility until radiation levels drop enough to send cat home (about 3-4 days) (Reference 1, 4)

- 95% cure rate

- side effects are rare

- small risk of hypothyroidism (too much tissue is destroyed and the cat will need thyroid supplements)

- owner must store wastes and soiled litter for 2 weeks

- cannot cuddle kitty for extended times for 2 weeks post discharge (e.g. cat cannot sleep on bed)

2. Medical Management with Methimazole (Reference 1)

- not a cure and the cat must receive daily medication to manage his hyperthyroidism

- methimazole is available in pills and transdermal gel

- frequent monitoring of T4 values is necessary

- side effects: vomiting, facial itching, liver failure

- tumor may continue to grow and become cancerous

3. Surgical Removal of Thyroid Gland (Reference 1)

The abnormal thyroid tissue is removed surgically, leaving the normal tissue alone. It is a procedure most surgeons can perform.

- up to 90% cure rate

- if not all the abnormal tissue is removed, hyperthyroidism can return

- general anesthesia can be risky in cats with cardiac issues and kidney disease

- there is a risk of damaging the adjacent parathyroid glands (regulate calcium in the body)

- risk of hypothyroidism if too much normal tissue is removed

4. Dietary therapy (Reference 1)

Hills y/d diet reduces the amount of thyroid hormone in the body by decreasing the amount of iodine in the cat’s food.

- response is 82% when on the diet

- safe for cats with kidney disease

- the cat cannot eat other foods

- only low-iodine treats and water can be used

- the cat will become hyperthyroid if he stops eating the diet

Both I-131 and thyroid surgery offer a cure for hyperthyroidism. However, both have a low risk of too much normal tissue being destroyed and the cat developing “hypothyroidism” as a consequence. The “hypothyroid” cat does not produce enough thyroid hormone and must be supplemented with daily oral medication for the rest of his/her life.

Both I-131 and surgery run the risk of unmasking more advanced kidney disease. Unlike medication or diet which can be adjusted or stopped, I-131 and surgery are permanent. Before recommending I-131 or surgery, some practitioners will conduct a trial with methimazole to assess kidney function when the hyperthyroidism is managed. However, some clinicians will opt to treat with I-131 even in the face of advanced kidney disease – persistent hyperthyroidism will further damage the kidneys if left untreated (Reference 5).

Diagnosing and treating hyperthyroidism in cats can be challenging. The presence of other diseases can mask hyperthyroidism and interfere with testing. I-131 is considered the gold standard for treating hyperthyroidism in cats. It does not carry the risks of surgery, avoids the side effects of methimazole and the difficulties of maintaining a strict prescription diet with a cat. Whichever treatment you choose, you have taken a step toward giving your hyperthyroid cat a healthier and longer life.

references

- Carney HC, Ward CR, Bailey SJ, et al. 2016 AAFP Guidelines for the Management of Feline Hyperthyroidism. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2016;18(5):400-416. doi:10.1177/1098612X16643252

- Geddes R, Aguiar J. Feline Comorbidities: Balancing hyperthyroidism and concurrent chronic kidney disease. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2022;24(7):641-650. doi:10.1177/1098612X221090390

- Kvitko-White, Heather. Recognizing and confirming feline hyperthyroidism. dvm360 March 2021 Volume 53, Feb 9, 2021. https://www.dvm360.com/view/recognizing-and-confirming-feline-hyperthyroidism (viewed 9/2023)

- Brooks, Wendy. Thyroid Treatment Using Radiotherapy for Cats. Veterinary Partner:VIN. Date Published: 01/01/2001

Date Reviewed/Revised: 09/05/2023. https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4951399 (viewed 9/2023) - Vaughan, F. and Wackerbarth, D. “Methimazole Trials: What Are They Good For?”, https://www.felinehtc.com/documents/Methimazole-Trials.pdf (viewed 9/2023)